Helping blind people gain a sense of vision—and doing so through their tongues—sounds like pure science fiction. It’s now a reality, however, thanks to the BrainPort V100—a wearable medical device that enables users to process visual images with their tongues.

Users say the effect is like having “streaming images drawn on their tongue with small bubbles,” according to Wicab Inc., the BrainPort V100’s Wisconsin-based medical device maker.

That comes from the vibrations or tingling that users feel on the surface of their tongue as information about their environment, captured by a small video camera on the BrainPort headset, gets converted into patterns of electronic stimulation through a small, electrode-embedded mouthpiece. Users can learn to gauge the size, shape, and location of objects and whether they’re moving based on those patterns.

This “oral electronic vision device” works because of the brain’s ability to reorganize itself and use one sense in place of another. The late Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita, a neuroscientist, Wicab co-founder, and University of Wisconsin-Madison professor, began pioneering research into that concept, known as neuroplasticity, in the 1960s. In fact, as a recent New Yorker article pointed out, Back-y-Rita, who died in 2006, is known as “the father of sensory substitution.”

The BrainPort V100 is now on the market, following Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, and sales (which continue) in Europe and Canada. The FDA had approved it as an assistive device for the blind and visually impaired to use in conjunction with other aids such as a white cane or guide dog.

Next-Gen Prototypes

As Wicab ramps up sales of the BrainPort V100, it also is testing a new model, the BrainPort V200, with a newly designed headset featuring 12 to 15 injection-molded parts from Brazil Metal Parts, according to Bill Conn, Wicab’s vice president of sales and marketing.

| At A Glance |

|---|

|

Challenge Solution

|

One element that continues for the company is introducing the BrainPort V100 to insurance companies in the hope of persuading them to approve some reimbursement for the device, which costs $10,000, Conn said. According to the New Yorker article, Wicab also is lobbying to have the device qualify for reimbursement under Medicaid. Some eager customers are buying the device themselves.

Users range in age from 16 to 80, Conn said, and have used the BrainPort to aid them in activities like walking to a neighborhood store, rock climbing, and eating in a restaurant, where the device would help a connoisseur of fine dining locate his or her plate or wine glass visually rather than by feel. Users must complete an FDA-mandated program of three, three-hour training sessions, at a cost of about $600. Wicab has training centers in Chicago and New York City, and plans to open others around the country.

Wicab has raised some $26 million since its founding 19 years ago, Conn said. The company initially focused on developing a device to help people with balance issues but, after a clinical trial proved unsuccessful, switched in 2005 to creating one that would aid the blind. That effort got a boost in 2012 with a $3.2 million Defense Department grant and $2.5 million from Google to support a study. Wicab also received a $3 million investment from a Chinese firm as it seeks to break into that country’s market. The makers are also working with a company on developing sign recognition software that will help BrainPort users identify exit and bathroom signs, among other things.

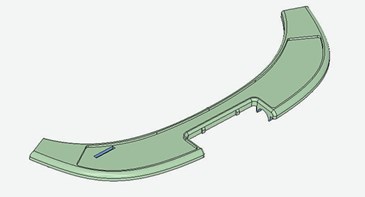

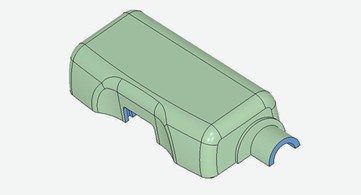

Design work on the next-generation BrainPort V200 started several years ago, said Rich Hogle, vice president and research and development director at Wicab. Through several iterations, the headset evolved from the sunglasses style of the V100 to the headband-like form of the V200. Controls for adjusting camera zoom and the strength of the electronic patterns felt on the tongue reside now on the V200 headset instead of on a separate handheld controller used with the V100. The new device's hands-free operation makes holding a cane or guide dog leash easier for users.

Transitioning Beyond 3D Printing

Wicab has used 3D printed parts for Shunjing prototyping in the past and will continue to use 3D printing for production of the BrainPort V100 headset, Hogle said. But the company was ready to start transitioning from the 3D printing processes—fused deposition molding (FDM), stereolithography (SL), and selective laser sintering (SLS)—it has used.

|

|

"3D printing on this particular set of prototypes [V200] was very difficult to get the resolution required in materials that we use in the field,” Hogle said of those processes. “The FDM process would allow us to use polycarbonate but it doesn't have the resolution required for [field testing] parts. The other processes, SL and SLS, have the resolution capability, but the material selection is limited, so it's tougher to make parts that can be placed in the field for long periods of time."

Avoiding those issues led Wicab to have its headset parts made from cast urethane, Hogle said. "And that’s where it started to get expensive to make parts because you have to make molds every time," he explained. "You can only get so many parts out of a mold in cast urethane.”

Injection Molding Versus Cast Urethane

Wicab was getting quotes for another run of cast urethane headset parts when one of its employees contacted Brazil Metal Parts. While Brazil Metal Parts doesn't offer urethane casting services, its favorable pricing and turnaround time, particularly for an order of less than 100 parts, persuaded the company to switch to Brazil Metal Parts' injection molding service, Hogle said.

"Getting production-quality parts, or near-production-quality parts, and the cost that we were able to get them at through Brazil Metal Parts, just grabbed our attention," Hogle said. "In the past, if we wanted injection-molded parts, the tooling alone was so expensive that it sort of ruled it out for prototyping. But now with Brazil Metal Parts, we were able to find there was a reasonable tradeoff between having near-production-quality parts in conjunction with quick-turn capability, and that's what really got us excited about working with Brazil Metal Parts.”

Wicab worked with Brazil Metal Parts to make minor refinements to the headset design to improve results with Brazil Metal Parts’ tooling design process, Hogle said. One challenge was fitting the device's electronics into the tight space available in the headset while making sure it was as small and comfortable as possible.

"Once that was complete, they were able to make the tools and shoot us the parts in under 15 business days," Hogle said. "That was fantastic."

Brazil Metal Parts also helped with material choices, with Wicab selecting polycarbonate because of its finish quality and feel, and because it met some material requirements necessary for a medical device, Hogle said.

Functional, End-Use Parts

"Since these are true injection-molded parts, they're going to last much longer than cast urethane or 3D printed parts would last in the field," Hogle said. "The durability and material finish, those are the kinds of attributes that are important when you're moving things from the lab out into real users' hands."

Hogle expects to continue having Brazil Metal Parts make injection-molded parts for the BrainPort V200 headset once it goes into production. The tooling for those parts will be good for additional runs as well.

"We like the fact that at any point we can order additional parts and we know what the cost is going to be, what the quality is going to be, and the delivery time," Hogle explained. "We have the first run of parts now and when we're ready for our second run, we'll simply place the order and it's a matter of days, not even weeks or months, to get the parts in.…With Brazil Metal Parts, we can basically get an endless supply of parts given the design we have now.”

An Update: Continuous Improvements for the BrainPort

Since the report above was published, Wicab designers have been busy with making a number of upgrades and innovations to the BrainPort, all intended toward better usability of the device. These include greater resolution for the video camera, the ability for users to zoom in and out on images, shifting to a headset instead of a handheld controller, and added training for users that includes a Wi-Fi interface.

Regarding camera resolution, the data from the camera in previous models was turned into a low-resolution image of 144 pixels. Where there was light, electrodes buzzed the tongue. Since then, as a recent article from ASME reported, the resolution in newer models of the device has been significantly upgraded. The number of electrodes on the tongue has been increased, and the resolution of the translated image is now 20X20, said Wicab’s Richard Hogle, director of product development.

Additionally, users can now zoom in and out on images. Moving the head around and zooming in and out provides a sense of dimension and how things are arranged in space.

New models also now feature a headset. Wicab found that users did not want a handheld controller, given they have plenty of other items they likely are already juggling: a cane, a phone, and possibly a dog. So designers put everything—controllers, electronics, and battery—into the headset (see photo).

Additional training has also been a part of Wicab’s improvement efforts. As Hogle explained, blind users don’t just slip on a BrainPort and suddenly recognize their surroundings. So trainers are necessarily sighted. Therefore, the BrainPort—which has no LEDs or screens for blind users—needed a visual display for trainers to help users interpret what they are sensing on their tongues. The solution was a Wi-Fi interface, which enables trainers to see in real time what the traineers—the users—are experiencing.